British Infantry Colours 1747-1800

Battalion Officer, Buckinghamshire Militia, 1793

by Sir William Young, 2nd Baronet (1749-1815)

Represented in this watercolor is an ensign carrying the second colour of the

Buckinghamshire

Militia.

The artist, Sir William Young of

North Dean, Buckinghamshire, was the elder

brother

of

Henry

Young (ca.1758-1777),

an ensign in the 62nd Regiment of Foot

who was

mortally

wounded in

action during the Battle of Freeman's Farm, New York, 19 September 1777.

British Infantry Colour Regulations

British infantry regiments of the line were supposed to carry a pair of colours—one, the first (or king's) colour, which was primarily meant to identify the carrying unit with the British nation, and the other, a second colour (usually referred to as a "regimental colour" today), which was primarily meant to identify the particular regiment carrying it. As accoutrements, colours were the private property of the regimental colonel and therefore not owned by the British government. Therefore, a degree of intra-regimental variety could be expected with the appearance of colours produced during the same time period.

The appearance of colours were first officially governed by various rules laid forth in the late 1740s-1751. As with other uniform aspects, colour regulations were updated in His Majesty's Warrant for the Regulation of Colours, Clothing, &c. of the Infantry dated St James, 19 December 1768:

The King's, or First Colour of every Regiment, is to be the great Union throughout.

The Second Colour to be the Colour of the Facing of the Regiment, with the Union in the Upper Canton; except those Regiments which are faced with Red, White, or Black. The Second Colour of those Regiments which are faced with Red or White, is to be the Red Cross of St George in a White Field, and the Union in the Upper Canton. The Second Colour of those which are faced with Black, is to be St. George's Cross throughout; Union in the Upper Canton; the Three other Cantons, Black.

In the Center of each Colour is to be painted, or embroidered, in Gold Roman Characters, the Number of the Rank of the Regiment within the Wreath of Roses and Thistles on the same Stalk; except those regiments which are allowed to wear any Royal Devices, or Antient Badges; on whose Colours the Rank of the Regiment is to be painted, or embroidered, towards the Upper Corner. The size of the Colours to be Six Feet Six inches flying, and Six Feet deep on the Pike. The Length of the Pike (Spear and Ferrel included) to be Nine Feet Ten Inches. The Cord and Tassels of the whole to be Crimson and Gold Mixed.

...

Devices and Badges of the Royal Regiments, and of the Six Old Corps.

First or Royal Regiment

In the Center of their Colours, the King's Cypher within the Circle of St. Andrew, and Crown over it. In the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the Thistle and Crown. The Distinction of the Colours of the second Battalion, is a Flaming Ray of Gold descending from the upper Corner of each Colour towards the Center.2d, or Queen's Royal Regiment

In the Center of each Colour, the Queen's Cypher on a Red Ground within the Garter, and Crown over it. In the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the Lamb, being the antient Badge of the Regiment.3d, or Buffs

In the Center of their Colours, the Dragon, being their Antient Badge, and the Rose and Crown in the Three Corners of their Second Colour.4th, or the King's own Royal Regiment

In the Center of their Colours, the King's Cypher on a Red Ground within the Garter, and Crown over it. In the Three Corners of their Second Colour, the Lion of England, being their Antient Badge.5th Regiment

In the Center of their Colours, St. George killing the Dragon, being their Antient Badge; and in the Three Corners of their Second Colour, the Rose and Crown.6th Regiment

In the Center of their Colours, the Antelope, being their Antient Badge; and in the Three Corners of their Second Colour, the Rose and Crown.7th, or Royal Fuzileers

In the Center of their Colours, the Rose within the Garter, and the Crown over it. The White Horse in the Corners of the Second Colour.8th, or King's Regiment

In the Center of their Colours, the White Horse on a Red Ground within the Garter, and Crown over it. In the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the King's Cypher and Crown.18th, or Royal Irish

In the Center of their Colours, the Harp in a Blue Field, and the Crown over it; and in the Three Corners of their Second Colour, the Lion of Nassau, King William the Third's Arms.21st, or Royal North British Fuzileers

In the Center of their Colours, the Thistle with the Circle of St. Andrew, and Crown over it; and in the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the King's Cypher and Crown.23d, or Royal Welch Fuzileers

In the Center of their Colours, the Device of the Prince of Wales, viz, Three Feathers issuing out of the Prince's Coronet. In the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the Badges of Edward the Black Prince, viz. Rising Sun, Red Dragon, and the Three Feathers in the Coronet. Motto, Ich Dien.27th, or Inniskilling Regiment

Allowed to wear, in the Center of their Colours, a Castle with Three Turrets; St. George's Colours flying in a Blue Field; and the Name Inniskilling over it.41st Regiment, or Invalids

In the Center of their Colours, the Rose and Thistle on a Red Ground, within the Garter, and Crown over it; in the Three Corners of their Second Colour, the King's Cypher and Crown.42d, or Royal Highlanders

In the Center of their Colours, the King's Cypher within the Garter, and Crown over it. Under it St. Andrew, with the Motto, Nemo me impune lacessit. In the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the King's Cypher and Crown.60th, or Royal Americans

In the Center of their Colours, the King's Cypher within the Garter, and Crown over it. In the Three Corners of the Second Colour, the King's Cypher and Crown. The Colours of the Second Battalion to be distinguished by a Flaming Ray of Gold descending from the Upper Corner of each Colour, towards the Center.

The particulars laid forth in the 1768 Warrant regarding line infantry colours were as sparse as they were with most other uniform appointments, and much could have been left subject to interpretation. However, despite this allowance (especially considering the myriad artistic representations which could come from vague language like a "Wreath of Roses and Thistles on the same Stalk"), enough period colours exist which instead demonstrate that there was apparently a great amount of design standardization within the army, so much so that distinct device pattern trends developed over the 1747-1800 period.

Both colours were supposed to be carried by ensigns chosen from those of the regiment. It is not entirely clear how regiments chose which ensigns carried the colours, although certain practices are alluded to in various records. For example, Ensign Thomas Hughes of the 53rd Regiment (A Journal by Thos: Hughes. E A Benians, ed. Cambridge University Press: 1947) wrote in his journal that "In April [1777] three German drafts of our Regt were shot for desertion at the head of the Colours, which being eldest Ensign I carried." No doubt colours would have been too cumbersome for most very young ensigns, and it took time for newly-commissioned ensigns to reach their new regiments (especially when serving abroad), so the pool of potential carriers would have been decreased further.

Due to the association of the rank of ensign with colours, an interesting idiom developed in 18th-century British lexicon: the act of “procuring a pair of colours.” Not to be taken literally, this phrase instead meant someone was to receive an ensigncy.

Wreath and Cartouche Pattern, 1747-ca.1770

Colours created during this timeframe were guided primarily by multiple regulations laid forth in the late 1740s-1751. Due to the lack of extant colours from this period, it is difficult to make generalizations on their actual appearance (as opposed to regulation appearance). However, from colours, colour device fragments, and drawings which do exist, the following traits seem to have been common during this period:

1) Regimental Roman numerals stand alone, without cartouche, background color, or "Regiment" term in the field.

2) Wreath design is small, symmetrical, circular, and closely wrapped around the regimental number.

3) Wreath designs of the early 1750s are simplistic when compared to those of the late 1750s/1760s; the simplistic wreath designs of the early 1750s are in fact reminiscent of the wreath designs used on late 18th-century colours (which see below).

4) Colour devises are almost universally embroidered.

Central Device, 1747-ca.1770, middle-type: Second Colour, 9th Regiment of Foot, 1757

Note the complex, circular symmetry of the wreath pattern embroidered closely upon itself.

Also,

the very plain

treatment

of the regimental number, without any accompanying

background

coloring,

cartouche or wording. As the regimental number, like the wreath, was embroidered through the

colour itself, the reverse of the colour would have been the number in reverse (in this case, "XI").

Central Device, 1747-ca.1770, late-type: Second Colour, 39th Regiment of Foot, ca.1768

This is an excellent example of a design bridging both the 1750s and 1770s pattern devices.

The

centerpiece now displays an organic cartouche, as well as the word "Regt." The wreath itself is no

longer

treated with near-perfect symmetry, but the design is still too tight, circular, and controlled

when

compared to those produced throughout the

1770s. Note the uncommon use of both garden

and

Tudor

roses

(the appearance of Tudor

roses was rare on 18th-century colour wreaths).

Wreath and Cartouche Pattern, ca.1770-ca.1785

Colours made during this period were governed by the specifications laid forth in His Majesty's Warrant for the Regulation of Colours, Clothing, &c. of the Infantry dated 1768 (as transcribed above). This is the first period it can be documented with certainty that despite expected device customization, extant colours demonstrate that an almost universal design was preferred by regimental colonels.

1) Regimental Roman numeral now universally appeared surmounted by "REGT."

2) Regimental number now appears on an organic red rococo cartouche outlined in gold, appliquéd to the colour (therefore, the lettering on the reverse of the colour would retain a proper orientation).

3) Wreath design is wild and fluid.

4) Wreath design is large and, like its predecessor, contained within the space of St. George's Cross.

5) Colour devices are almost universally embroidered.

Central Device, ca.1770-ca.1785, early-type: King's Colour, 33rd Regiment of Foot, 1771

Note the wreath designs of this colour and the one below. While differing in artistic respects and

certainly executed by different hands, there can be no doubt that the same pattern was used.

Central Device, ca.1770-ca.1785, early-type: King's Colour, 12th Regiment of Foot, 1772

Note that while the tendrils of this organic cartouche are not as refined as those of the 1771 king's

colour

of the 33rd Regiment, their endpoints were brilliantly manipulated to wrap around the

branches of

the

surrounding wreath. "Stabilis" was a longtime motto of the 12th Regiment, and although

disallowed

by regulation, the regiment retained the motto on their 1772 colours. Ironically, this regiment

was

one

of a

select few (along with the 39th, 56th, and 58th) granted an official allowance in 1784

to

bear the battle

honor "Gibraltar" on their second colour.

Central Device, ca.1770-ca.1785, late-type: Second Colour, 93rd Regiment of Foot, 1781

This colour's cartouche is controlled and less fluid than those found on its 1770s predecessors. The

same holds true

with

the wreath itself; while still retaining a wild pattern, styling is regressing toward

a more simplistic symmetrical arrangement reminiscent of those from the early 1750s. It was at this

time

that king's colour wreaths began to extend beyond the confines of the cross of St. George. This

can be

seen in John Copley's 1783 painting, The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781, which

prominently

depicts the colours of the 95th Regiment. This styling may have been particular

to high number

wartime regiments only.

Wreath and Cartouche Pattern, ca.1785-1800

The previous colour exemplified a late-war cartouche and wreath arrangement. The visible trend toward a symmetrical wreath and a controlled, less organic cartouche was apparent and by the mid 1780s, a new styling was achieved which would retain almost universal popularity into the 19th century.

1) Regimental Roman numeral is now surmounts "REGT." A "GR" cypher and/or a crown is sometimes added.

2) The organic, tendril-like cartouche is replaced by a red symmetric shield outlined in gold.

3) Wreath design is symmetrical; later wreath designs of this type tend toward sparsity.

4) Wreath design is larger and purposefully extends outside the bounds of the Cross of St. George.

5) Colour device is more commonly painted instead of embroidered.

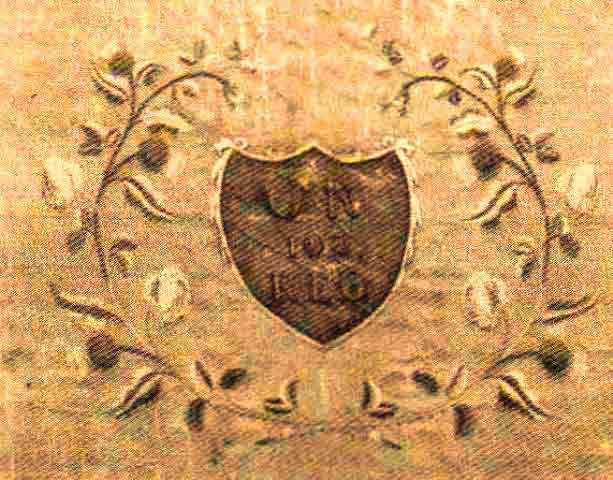

Device pattern, ca.1785-ca.1800, early type: King's Colour, 55th Regiment of Foot, 1786

photo by

John Neitz; from the 55th (Westmoreland) Regiment of Foot entry on Wikipedia.com

Device pattern, ca.1785-ca.1800, late type: Second Colour, 102nd Regiment of Foot, 1794

As with the 55th Regiment colour above, this colour employs a "GR" cypher within the shield

above

the regimental number, but without a crown. Note the simplicity of this colour's wreath.

British Infantry Colours on Campaign during the

American War for Independence

Information regarding colour carrying by British regiments during the war is difficult to come by. On the surface, the surviving (albeit scanty) evidence appears contradictory; written descriptions imply or outright state that British regiments left their colours in storage during the campaign season, but artifacts and inventories prove that in fact some regiments carried their colours on campaign.

Unfortunately, explicit British-recorded references to the armies in general or regiments in particular carrying colours is rare. Thankfully, German officers were not as silent on the matter. In fact, there are many German accounts, from different sources and commenting upon different campaigns, which speak to the exact topic. It is interesting that every German correspondent referred to the same predicament, and an example of this, written by an unknown Braunschweig officer to an unknown correspondent, in a letter dated St Anne, Canada, March/April 1777 (Letters from America 1776-1779. Ray W Pettengill, trans. Kennikat Press, Port Washington, NY: 1964), appears as follows:

Here we have a special way of waging war which departs utterly from our system. Our infantry can only operate two deep, and a man must have eighteen inches space either side to be able to march in line through woods and brush. We cannot use cavalry at all, so our dragoons have to rely on their own legs. Our standards bother us a lot, and no English regiment brought any along.

The British forces garrison at Rhode Island was not immune to this same phenomenon. In a January 1778 letter, General

Friedrich Wilhelm

von Lossberg, who commanded

the German contingent there, wrote the following (our thanks to Don Hagist for the following transcript):

It would be far better if they [the Island's northern posts] were occupied by detachments of the regiments, but that is not their way of doing things; they [British] do everything by regiments, they have their colors with them only when quartered, while we carry them with us wherever the regiments go. This is bad whenever a regiment is split up and put into redoubts which are not closely together.

Von Lossberg was adamant about this point. Within less than a year, he again wrote about his concerns in a December 1778 letter (our thanks to Don Hagist for the following transcript):

The country is bad for fighting. Nothing worries me more than the colors, for the regiments cannot stay together in an attack because of the many walls, swamps, and stone cliffs. The English cannot lose their colours, for they do not carry them with them.

The common theme amongst the German correspondents is that the German regiments (of various states) carried their colours, which gave them no end of trouble due to the new-style, often fragmentary movements of a battalion's companies over broken ground. The British, far more adept at adopting this new tactical doctrine, kept their colours in storage so they would not be an encumbrance during these movements. This works well as a generality—the German officers certainly made note that this was a practice of British regiments—but solid examples of campaign colour carrying betray the absolute veracity of the various German claims.

Although the British are strangely silent on the question of the use of colours on campaign, there are nevertheless some examples. Probably most famous comes from the memoir of Sergeant Roger Lambs, in which he states that he carried a colour of his regiment, the 23rd or Royal Welch Fuzileers, in the 16 August 1780 Battle of Camden. Ironically, the most plentiful and best documented sources of British colour carrying is in the form of inventories of colours captured by rebels. For example, the 7th or Royal Fusiliers lost both their colours when they surrendered Fort Chambly, Québec, on 20 October 1775, the 17th Regiment lost both its colours at Stony Point, New York, on 16 July 1779, the 7th or Royal Fusiliers lost their colours...again...at Cowpens, South Carolina, on 17 January 1781, and several British regiments lost their colours at the great Yorktown, Virginia, surrender on 19 October 1781. Clearly, therefore, there are examples of colours brought with British regiments on campaign, and even carried onto the field of battle.

King's Colour, 7th or Royal Fusiliers Regiment

West Point Museum

This colour, along with its companion, was captured from the regiment at the surrender of Fort Chambly

in October

1775 during the rebels' invasion of Canada. Note the rather primitive treatment of the center

device,

and the reverse

regimental number "IIV" in the upper left corner. The central device, embroidered

and

appliquéd to both sides, therefore

retains proper letter and design orientation on both the obverse and

reverse of the colour (whereas the regimental number

was painted). As a

royal regiment, this colour bears

neither a wreath, cartouche, nor shield,

but instead the special emblems

approved by regulation.

Colours in Lieutenant-General John Burgoyne's

Army

from Canada, 1777

The question of whether or not regiments in Lieutenant-General Burgoyne's Army from Canada brought their colours on campaign is almost as old as the campaign itself. It has been demonstrated that British regiments of the 13 colonies armies fighting in America sometimes left their colours in storage and sometimes brought them on campaign. But what practice did Burgoyne's regiments follow?

No colours were surrendered to the rebels at Saratoga on 17 October 1777, nor were any colour pikes discovered by the rebels as a sign of there having been colours with the army. After receiving a report of all militaria captured at Saratoga, the rebel congress was less than impressed with their take and drafted a series of questions for their commander in the field, Major General Horatio Gates, to answer. First amongst the questions, passed in a resolution by congress dated 22 November 1777, was “What is become of the standards belonging to the respective regiments in General Burgoyne's army?” Clearly, congress was concerned. Gates's reply, in a letter to the rebel president of Congress dated 3 December 1777, was adamant, claiming that "Respecting the standards, General Burgoyne declared upon his Honor, that the Colours of the Regiments were left in Canada." But the affair was far from concluded. Congress set about to find proof that Burgoyne had lied, and that the colours had been improperly secreted away. Soon after receiving Gates's response, congress, in the infamous 27 December 1777 session which condemned the Convention Army to de facto prisoner of war status, passed its three resolutions to justify why the treaty was being breeched. According to their third resolution:

Resolved, That there is just ground of suspicion notwithstanding the declaration of Lieutenant General Burgoyne that all the standards and colours belonging to his army were not left in Canada previous to the march of the army from that province.

This was a very damning charge, and one would expect that the rebel congress had clear proof to justify claiming it. While it's uncertain exactly how congress came to the conclusion they did, what is certain is that they were in fact correct. One major source was the rebel commander of the Continental Army's Eastern Department, Major General William Heath. In a letter from Heath to rebel president of congress Henry Laurens, dated Head Quarters, Boston, 6 June 1778 (William Heath Papers):

It has been frequently reported Since the Convention of Saratoga that the Colours of the Several British and Foreign [German] Regts were either Sent to Canada or Burnt. I take the Liberty to enclose the Declaration of Several Officers lately Come off from the Foreign Troops at winter Hill one of them is a Lieut. The Colours most Probably are Still among the Baggage. The pleasure of Congress in this and all other respects, shall be Immediately Carried into Execution when notified of it by him.

Laurens, in turn, transmitted this information to the rebel governor of New York State, George Clinton, in which he also included a copy of the declaration by German officers alluded to by Heath, above (George Clinton Papers):

York Town 25th June 1778.

Sir, I beg leave to refer Your Excellency to my last of the 20th by Dodd.

Inclosed Your Excellency will be pleased to receive a Copy of an information relative to the Colours of the Army late General Burgoyne's which ought to have been surrendered at the Convention of Saratoga.

General Heath is directed by Congress to continue his endeavors for obtaining further evidence & if possible the remains of the Standards.

I have the honor to be With great Esteem & Respect Sir Your Excellency's Most Obedient serv't

Henry Laurens, President of Congress.

His Excellency Governor Clinton New York.

The copy of information inclosed in a letter from Major General Heath of 6 June 1778:

After the German army of Fritmanfirm had moved or retreated to Saratoga and were surrounded with the provincials—Then major genl. viz. Riedesel gave order That genl. Burgoyne had commanded the standards should be burnt, that they might not fall into the hands of the provincials. The following night contra orders were given that genl. Burgoyne would fight his way through, on which he received orders to cut the staffs from the standards & to put them in the covered waggon to go with the army. The same night major V Mengen came to me and said I should, in case I was asked, inform the other freed corps that we had burnt the standards, so that we might be unanimous were they are now—we suppose on Prospect Hill.

Ernst Frederick Segern.

We hereby witness that the standards were not burnt but are brought hence by favour.

H. Siebert lieut.

John Frederick Remeke surgeon.

Just over one month later, Laurens received the following letter from a foreign-born captain of Engineers in the rebel service, Johann Christian Senf, dated Charlestown, 5 August 1778 (papers of the Continental Congress; spelling per original document):

His Excellency the President

Sir,

Obedient to your Excellency's orders I have the Honour to give your Excellency some little Intelligence about Genl Bourgoyne's Army.

Every regular Regiment of Genl Bourgoyne's Army brought their colours along with them from Canada. Genl Bourgoyne left one English & one German Regt at Tienderoga in Garrison. His Line was also besides Avant-Corps (wich had no colours)

5 English Regt pr Regt 2 colours—10 colours.

4 German Regt, pr Regt 5 [colours]—20 [colours]30 colours [total].

I was told at Albany that by Genl Bourgoyne's Orders in the time of the capitulation, by wich I was allready takken prisoner, all the German colours had been burnt, and after they had capitulated some of the English Kings—colours had been carried out of the camp in some officers Baggage—

All the Arms in Bourgoyne's Army have been continually in good order, (wich allways is the belief from a regular army) I was told, that the soldiers destroyed in the time of the capitulation &c. &c.

I am with the greatest Respect

Sir

Your Excellency's

most humble & obedient Servant

Christn Senf

Capt Engr

Although his spelling was poor, and he was apparently fooled by the burning of German colour pikes (not the colours themselves, which see below), Senf's claims regarding numbers of colours per regiment and regiment type, as well as the specificity regarding the disposition of British King's colours in particular, implies that his claims were not invented. The five British regiments claimed by Senf to have brought their colours would have been the 9th, 20th, 21st or Royal North British Fusiliers, the 47th, and 62nd Regiments of Foot (the 53rd remained at Ticonderoga). As part of the Advanced Corps, the 24th Regiment apparently did not campaign with their colours.

British and German evidence in support of Burgoyne's regiments carrying colours is incontrovertible. The first dated evidence is in the form of an incriminating general order to Burgoyne's Army from Canada dated Camp at Skenesborough House, New York, 19 July 1777:

A Captain's Guard with the Colours of the Oldest Regiment to mount tomorrow upon the Congress with the Indian Nations. This Guard is to be at the Indian Camp by half past eight tomorrow morning.

This order not only confirms that colours were being carried, but suggests that multiple regiments had their colours with them. What may also be implied is that the army command was not clear or certain as to which regiments had their colours on the campaign; hence, their choice to use language which specifically chose the regiment without having to know which one it was in advance, as the order would have placed the burden upon the regimental commanders to figure out who qualified.

A rather elaborately-detailed letter written by Brigadier-General Simon Fraser to John Robinson dated “Camp at Skeensborough on Wood Creek, 13 July, 1777” (Abergavenney Manuscripts, Eridge Castle), recorded the events of the preceding week. Related to the 6 July 1777 capture of Forts Ticonderoga and Independence:

about 3 o'clock of the morning of that day two Deserters came to my advanced posts and reported that the Enemy were abandoning Ticonteroga, and the works on Mount Independence, at first I conceived it to be a Ruse to bring a corps of men within reach of grape shot, I dispatched an officer with this information to Genl. Burgoyne, then on board the Royal George, I ordered the Brigade to accoutre without noise or delay, to march to a certain situation & wait further directions, I sent for the Colors of the 9th Regiment then encamped near me, the 24th not having theirs on the field, and I moved in person with the Engineer & a small party towards the lines, desiring my Piquets to follow me at some distance; I found the report proved true, that they made a combined retreat by land towards Castletown & by water to Skeensborough, leaving all their Cannon, a great quantity of provisions and ammunition destroying nothing but the Bridge of communications between Ticonteroga & Mount Independence, I got planks, by means of which I cross'd my Brigade to the Mount leaving a sufficient number to guard the stores at Ticonteroga, having hoisted a Colour of the 9th Regiment [ie, the second colour] in the old French redoubt, the Kings Colour was soon after displayed on the Mount....

Fraser's letter admits some very important points:

• The 9th Regiment in fact brought its colours, and the colours were present with the regiment in its encampment.

• The 24th Regiment did not have their colours "in the field." It's unclear from the language if the 24th's colours remained in Canada, were with the baggage in the rear of the army, or were simply back in the regiment's camp. As the 24th Regiment served directly with the elite British grenadier and light infantry battalions—battalions without colours—it is probable that the former explanation is likely. Such would have been in keeping with the purpose of Fraser's Advanced Corps, the design of which was to move with the greatest speed and with as little encumbrance as possible, in advance of the army. This theory is confirmed in Senf's letter transcribed above.

• It was apparently, and perhaps surprisingly, acceptable for one corps to borrow the colours of another out of necessity.

Its odd that almost every further reference to British colours with the Army from Canada relate to those of the 9th Regiment. Even in the 1823 obituary of Lieutenant-General Gonville Bromhead, published in The Annual Biography and Obituary for the Year 1823 (volume VII, A & R Spottiswoode, London: 1823), particular reference to the colours of the 9th Regiment in the Battle of Freeman's farm was made (it bears noting that Bromhead was then a lieutenant in the 62nd Regiment):

on the 19th of September, 1777, at the battle of Freeman's Farm, nearly the whole of his regiment [ie, the 62nd Regiment] was destroyed, himself and two privates being the only two persons of the company to which he belonged, that were not either killed or wounded. On this occasion he was attached by Sir Francis Clerke [Burgoyne's primary aid-de-camp], to the colours of the 9th regiment, which was then advancing.

Regimental tradition holds that both colours of the 9th Regiment were saved from rebel hands by Lieutenant-Colonel John Hill, who secreted them away in his personal baggage. Upon returning to England, Hill presented the colours to the king, who granted them to Hill as a gift and made him an aid-de-camp. This is a likely scenario, as no colours were surrendered at Saratoga. And as the Saratoga Convention stipulated that personal baggage was off limits to search or seizure by the rebel victors, such would have been possible.

Senf's claim that "after they [the British] had capitulated some of the English Kings—colours had been carried out of the camp in some officers Baggage" is specific: some of the British officers saved their unit's King's colours (and as expected, secreted in personal baggage). Since King's colours were valued over second colours, and there are a disproportional abundance of extant King's colours of regiments which surrendered at Saratoga, it is possible that the British in fact burned their second colours, and some saved their King's colours. Perhaps, therefore, Lieutenant-Colonel Hill presented only one—the 9th Regiment's King's colour—at court upon his return to England.

Device of the King's Colour, 9th Regiment of Foot, 1772

Although the 9th Regiment was inspected as having receiving its colours in 1772, tradition holds that the

second

colour

of the pair, while new, incorporated the centerpiece of the 1757-issue second colour (which

see above).

Note that the

patterning of this wreath is directly opposite those displayed on the 12th and 33rd

Regiment colours above; this is due to the fact that the design was embroidered through the silk of the

colour itself. Pike sleeve orientation proves that this view is of the reverse of the colour, while the views

presented of the 12th and 33rd Regiments are the obverse.

Thankfully, the Germans with the Army from Canada were, as with the main army, more meticulous when writing about the trials and tribulations concerning their colours. Accordingly, we find that the 9th Regiment was not the only one to have its colours mounted at Fort Ticonderoga. According to the 6 July 1777 journal entry of Lieutenant August Wilhelm Du Roi, the elder, of the Braunschweig Regiment Prinz Friedrich (Journal of Du Roi the Elder. Charlotte Epping, trans. D Appleton & Company, New York: 1911):

We disembarked and marched with the band playing to Fort Ticonderoga. The colours of the enemy were hauled down at once, and the colours of the regiment hoisted on one of the bastions.

A fellow officer of the same regiment, Ensign Julius Friederich von Hille, also recorded the same happy occurrence in the 6 July 1777 entry of his journal (The American Revolution, Garrison Life in French Canada and New York. Dr Helga Doblin, Trans. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT: 1993). Writing in the third person, he proudly stated that:

The regt. disembarked and marched to Fort Ticonderoga (Carillon) and E[nsign] von Hille, who was on guard duty that day, had the honor of planting the banner of our regmts. onto the rampart of Fort Ticonderoga.

As this event must therefore have been an important one for the Braunschweig Regiment Prinz Friedrich, the regiment's lieutenant colonel, Julius Christian Prätorius, also recorded the event in the 6 July 1777 entry of his journal. Thankfully, he identified which colour was put in place when he wrote "I immediately had the 2 flags of the Rebels taken down and the Leib flag of the Pr. Friedr. hoisted." Dragoon squadron surgeon Julius Friedrich Wasmus recorded another "colour" incident in his journal, dated 9 August 1777 (An Eyewitness Account of the American Revolution and New England Life. Dr Helga Doblin, trans. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT: 1990):

At midnight, the standards of our regiment [Braunschweig Dragoon Regiment Prinz Ludwig] were taken to the headquarters of our general; this is an indication that we are to be assigned to an important expedition.

Wasmus's assumption that an "important expedition" awaited turned out to be an understatement, although not the type he and his fellow Germans hoped for; the expedition intended for most of the Dragoon Regiment and detachments of other corps was Bennington. Although the regiment was almost completely annihilated in that battle, the four colours of the regiment remained safely in camp. This is significant, as this means that the overconfident detachment did not bring the colours of the centerpiece regiment of that detachment. In a letter from Hessen-Hanau Brigadier Wilhelm Rudolph von Gall to Erbprinz Wilhelm, Landgraf of Hessen-Hanau, dated camp at John's House, 29 August 1777, he wrote that "fortunately the dragoons had not taken their colours with them, but left them behind with a detachment [of the dragoon regiment]; these were saved." In von Hille's 23 August 1777 journal entry, he wrote that the "4 standards of the Dragoon Regiment were given over to the Regt. Pr. Fr. because the former had been made prisoners in the expedition to St. Croix Mill on the 16th and [before setting out] had left the standards behind in camp." Although the remnants of one of the four squadrons of the dragoon regiment remained with Burgoyne's army, they were not entrusted with retaining their colour, nor those of the other three squadrons, for the rest of the Northern Campaign.

The Germans were also the only writers to confirm with certainty that they retained their colours right up until the surrender. But what did they do with them? The recorder of the Specht Brigade journal, Lieutenant Anton Du Roi, entered in his 16 October 1777 entry that (The Specht Journal. Dr Helga Doblin, trans. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT: 1995) "At night, the cloth and tassels had to be taken off the flag poles; the latter were burned, the former packed." This was confirmed in the 17 October 1777 entry of the official Headquarters Journal of the Braunschweig Corps: "Last night the flags of all the regiments in the army were made away with, so as not to surrender any trophies to the enemy, which were too beautiful for them." Baroness von Riedesel, in her famous memoir, wrote of the incident as she had a direct hand in it

(Baroness von Riedesel and the American Revolution, journal and correspondence of a tour of duty 1776-1783. Marvin Brown, trans. University of North Carolina Press: 1965):

I had to conceive some means now for bringing the flags of our German regiments into safety. We had told the Americans in Saratoga that they had been burned, which annoyed them very much at first, but they said nothing more about it. In fact, only the staves had been burned, and the flags themselves had been hidden. My husband entrusted me with this secret and assigned me the task of keeping the flags concealed. I got a trustworthy tailor, locked myself up in a room with him, and together we made a mattress, in which we sewed up all the flags. Captain [Laurentius] O'Connell [an aid-de-camp to Major General von Riedesel] was sent to New York on some pretext and took the mattress with him as part of his bedding. He left the mattress in Halifax, where we got it and took it with us when we went from New York to Canada. In order to avoid all suspicion, if our ship should be captured, I took the mattress into my cabin and slept on these badges on honor all through the rest of the trip to Canada.

No doubt the Baroness's statement that "We had told the Americans in Saratoga that they [colours] had been burned" was accurate and had the effect of fooling many, including Senf (his letter transcribed above), as he admitted to that very point in his report to the rebel president of congress. The four German regiments of Burgoyne's force which retained their colours were the Braunschweig Regiments von Riedesel, von Rhetz, Specht, and the Hessen-Hanau Regiment Erbprintz. As each musketeer company had its own colour (and there were five musketeer companies per battalion), the Baroness and the tailor secreted a total of 20 colours in the bedding! It bears noting that the official Headquarters Journal of the Braunschweig Corps, which was a daily accounting of the progress of the campaign meant for the Duke of Braunschweig himself, stated that "the flags of all the regiments in the army" were thusly taken off their poles and hidden away, and not only German colours. It is therefore true that most of the British (and probably all the German) regiments had their colours during the Northern Campaign of 1777, and by the time of the surrender, those same regiments probably still had them. Anecdotes related to the saving of the 9th Regiment colours are plentiful, and it's probable that other British regiments with Burgoyne's army followed suit. Regarding the German regiments, evidence goes beyond anecdotal, and the colours and tassels were in fact secreted away with unsearchable baggage while the pikes were burned in order to eliminate evidence.

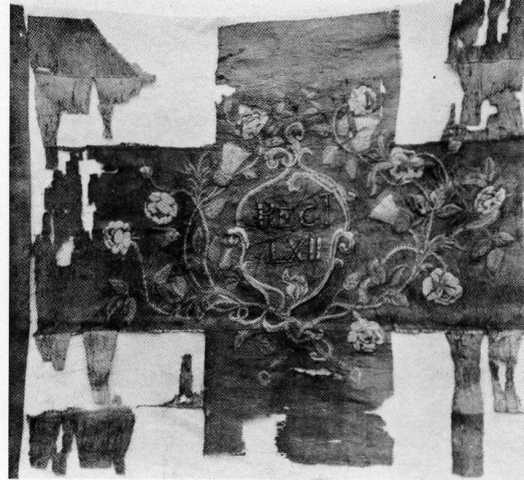

Device of the King's Colour, 62nd Regiment of Foot, 1772

Saved from the hands of the victorious rebels, this 62nd Regiment's King's Colour was saved by the regiment's

officers before they were forced to surrender at Saratoga. By the time this photograph was taken, all that remained

of

the colour was the device, the central portion of the Cross of St. George, and various fragments. As the

colour

sleeve (seen at left) was detached from the rest of the colour, it is probable that this is the reverse of the

colour.

Our thanks to Martin McIntyre of The Wardrobe,

The Rifles (Berkshire and Wiltshire) Museum for both

the photograph and corroborative documentation.